KATHMANDU (15 March 2017) – Another important factor for the timely transition from bullet to ballot in Nepal was the highly sensitive geo-political positioning of the country sandwitched between two huge states of India and China. A prolonged armed conflict could have a spill over effect in the neighbourhood leading to serious conflagration in the region.

……………..

It is an honor to be among such eminent personalities both in the panel as well as in the audience.

I would like to thank the organizers for giving me this opportunity to share my thoughts on a theme titled “Bullet to Ballot” that seems equally relevant in the entire South Asian region.

In this speech I would like to primarily focus on the transitional nature of Maoist politics in Nepal during the last two decade as the theme itself suggests —why did the Maoists fighting a protracted People’s War came to a peaceful democratic process? How did it become possible? What have been the implications? And, most importantly, what does the Nepalese experience offer to others involved in the similar democratization process?

- Firstly, I need to point out that the transitional nature of Nepalese politics is ongoing, where some of the longstanding problems continue to unsettle national politics. Today, these challenges have manifested themselves in new ways. Thereby, posing serious questions regarding the tenability of implementation of the new constitution of 2015.

I, myself, after being at the forefront of the Maoist armed struggle and thereafter playing a leading role in the constitution making process, have left the Maoist party. After the promulgation of the new constitution, I have chosen a new political course with the aim of establishing an alternative political force (Naya Shakti) that could genuinely and rightfully address the new challenges of this new era.

Therefore, since the task of democratizing our society and polity has not ended with the transition from bullet to ballot, I look very much forward to hearing what the panelists from Sri Lanka and different parts of India have to share with us today.

- The expression “Bullet to Ballot” in the plain and literal sense suggests a shift in the use of political tools or the means of conducting politics.

Bullet figuratively implies the violent method and the ballot suggests the embracing of nonviolent mode of doing politics.

Theoretically and philosophically, it is a tremendously challenging task to arrive at a conclusive understanding regarding violence and non-violence.

Once, we enter into this debate, it does not end merely at the desirability or undesirability of using violent or non-violent methods, or whether in any given circumstances violence can be treated as a legitimate act or an act of last resort.

Most debates on this issue very often assume a moralistic or ethical overtone leading many theorists to argue over calculations of human cost or the economic and ecological costs of wars.

But let me not enter into such a debate regarding the calculability of consequences of violent acts.

These are extremely contested concepts and any attempt to make an absolute moral judgment can become a rather tricky task.

So, instead of treating these terms in their absolute sense, I think it would be more worthwhile to talk about the grey areas, or the avenues where politics assumes a rather complex character.

This is because everyday politics is very often about these shades of grey where not everything presents itself as black and white.

And it is this obscure area that opens up new possibilities for us to think and act differently about how we can restructure the democratic space to accommodate those that remain outside it.

- This leads me to discuss the specific context of Nepal and the Nepali Maoists. The shift in Maoist politics from an armed struggle towards the constitutional site became possible because of couple of reasons.

The first thing that needs to be highlighted is that the Maoist movement in Nepal was a political movement informed by ideas of social justice, socio-economic programs that attracted widespread support among the people.

What also needs to be recognized is that this movement in many ways resonated the aspiration of past struggles and revolts in Nepalese history against autocratic rulers, making a call for democracy.

As Prof. Muni, who is also present here, has often stated, the Maoist movement was a product of Nepal’s existing socio-economic and political context.

Politically, the struggle between monarchy and democracy has been the main contradiction in Nepal’s modern history. All the major political parties in Nepal since their formative days have led popular struggles against autocratic regimes in one form or the other.

With the end of Rana oligarchy in 1950, a space for parliamentary democracy was opened up for the first time in Nepal’s history.

Let me point out here one major difference between the Nepalese case and the Indian case.

While democratic institution making and functioning in India remained uninterrupted post-independence, in Nepal a major breach took place within a decade of introduction of parliamentary democracy.

And this happened precisely because of the existence of the institution of monarchy. More specifically, when King Mahendra assumed an autocratic role under the disguise of a party-less Panchayat system in 1960.

This is the backdrop against which parties like Nepali Congress and the communist parties conducted their politics in Nepal.

During the mass uprising of 1990, it was primarily this struggle between monarchy and democracy that shaped the demands of the people and the political parties. However, this too ended in a constitutional compromise between the parliamentary parties and the Shah monarchy.

The fallacy of this institutional compromise with the King was exposed when it became possible for an autocratic monarchy to emerge from within the parliamentary system, that is, when Gyanendra Shah took over complete executive powers in 2005.

The Maoists which initiated their armed struggle in 1996 identified this union between the monarchy and traditional parliamentary parties as a major fault line in Nepalese politics which had ramifications in Nepal’s poor socio-economic conditions as well.

Politicians and scholars alike have not hesitated to acknowledge the competence with which the Nepali Maoists exposed this triangular contestation between the monarchy, the parliamentary parties and the revolutionaries in Nepal’s concrete historical context.

After the Royal coup of 2005, the Maoists were the first to call for an effective and coordinated program among the democratic forces for resistance against the autocratic monarchy.

And it was this peculiar initiative which opened up the possibility for the Maoists and parliamentary parties to arrive at a consensus regarding the abolition of monarchy and to forge a common commitment towards “full democracy” or purna loktantra.

In continuation with what Clausewitz famously said, both the bullet and the ballot are continuation of politics by other means. The call for making a new constitution through a constituent assembly elected by the people that had remained an unfulfilled aspiration during the past uprisings was taken up by the Maoists in the new context.

Therefore, one of the uniqueness of Maoist politics in Nepal is that they had a pivotal role to play in the final battle of monarchy versus democracy, through both the bullet and the ballot.

Infact, unlike what one would normally expect, it was actually the Maoists who made a call for using the ballot to draft a new constitution.

- Let me, here, share with you that it was not just circumstantial arrangement of events or a mere reaction to political incidents such as the Royal takeover that enabled the Maoists to talk about making democratic innovations.

Theoretically too, there have been rich debates within the Maoist party about the need for communists to take democracy seriously, not only tactically but also substantively.

Therefore, apart from exposing the problems intrinsic to the system of constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy, the Maoists were engaged in a project of democratizing themselves as well. This is a crucial point.

Of course, not all Maoist leaders agreed on this point. There were serious differences among the top leaders regarding democratization of the party as well as making a democratic alliance with the parliamentary parties. In fact, I was one of the first and few to push for democratic innovations within the party as well as in relation to other parties.

Nevertheless, these views were subsequently adopted by the party itself leading to the seminal document entitled “Development of Democracy in the 21st century”.

Here the Maoists indulged in self-introspection and asked themselves how they could avoid the mistakes of previous socialist-communist regimes. Towards this end, significant resolutions were made to redefine and “democratize” the relationship between the leaders and the led, between various organs of their party, and also amongst the leaders themselves.

But the most noteworthy statements were about the party’s views regarding state power and political freedom. The Nepali Maoists decided that, when in power, they would allow rival political parties to mobilize and compete with the revolutionary party. Therefore, the Maoist party would also have to acquire mandate from people through elections, otherwise they themselves would degenerate into an authoritarian bureaucratic organization.

- I have considered it important to share with you these specificities because without an insight into these theoretical and political innovations within the Maoist party, our understanding of the transition in Maoist politics from the bullet to the ballot would be lopsided and misunderstood.

- Another important factor for the timely transition from bullet to ballot in Nepal was the highly sensitive geo-political positioning of the country sandwitched between two huge states of India and China. A prolonged armed conflict could have a spill over effect in the neighbourhood leading to serious conflagration in the region.

- In cases of “complete win-lose” or “zero-sum” conflicts, a new constitution can become the symbol of a new political beginning after the past regime has been brought to an end. Political theorists call this the “replacement model”.

However, political conflicts may often also end in a stalemate without any side emerging as a clear “winner” or “loser”. In such cases, constitution making can become a part of a peace pact or ceasefire agreement. The constitution could then be an outcome of a negotiated pact or a compromise between the past rulers and the new political force.

Nepal’s peace process and constitution making stands somewhere in between these two approaches.

By ousting monarchy and establishing a republic, Nepal’s new constitution marked a rupture from the past political regime in one way. But, on the other hand, there was also an institutional compromise regarding parliamentary democracy between the Maoists and the non-Maoist parties.

In the process, the parliamentary parties had to discard some of their “old” political beliefs and embrace more radical notions of socio-economic transformation than traditionally adjustable in liberal democracy. For instance, commitments towards federalism, proportional representation, inclusive and participatory democracy, land reform, etc. were made.

On the other hand, the Maoists also had to suspend some of their ideological positions and accept certain ideas conventionally associated with liberal democracy such as protection of private property, rule of law, separation of power, etc.

These commitments, understandings, or agreements between the Maoists and the non-Maoists were instrumental in laying the foundation for the prolonged peace process and constitution making in Nepal. In other words, these were the basic guidelines for the transition from bullet to ballot in Nepal.

- If we remind ourselves of these specific original objectives, then it is not very difficult to understand the complications in Nepal’s constitution making process or its democratic transition. This will enable us to understand the reasons behind the uprisings in Terai-Madhes regions and dissatisfaction among the indigenous population even after the promulgation of the new constitution

- If structural origins of conflict remain unaddressed, and democratic spaces for articulation of genuine socio-economic and political demands are not made available to people, then the sustainability of any society’s transition towards a stable, peaceful and functional democracy can remain vulnerable.

This is one of the most important lessons from Nepal’s recent experience.

However, we must also refrain from making generalizations. Because experiences regarding transition from bullet to ballot are time and context specific. The Nepali case, at best, can be considered a reference from where lessons can be learned and unlearned.

- Let me end by saying that the tasks of democratic transition is a continuous process of progression. So, even though creation of new political institutions and constitutional remedies are crucial aspects, a nation must always make relentless efforts to continuously democratize its relationship with its people.

The new mission that I have recently embarked upon is guided by this very understanding. The idea of Naya Shakti not only as an alternative political party but also as a movement for deepening democracy is a natural corollary to transition from bullet to ballot.

As Christopher Columbus had once said, “You can never cross the ocean unless you have the courage to lose sight of the shore.” I have mustered the courage to lose sight of the “shore” of bullet and attempted to cross the ocean of progressive transformation of the world through the ballot. Let us all join hands to create objective conditions for peace, prosperity, equality, and justice so that nobody has to ever resort to the bullet.

Thank you all for a patient hearing.

15 March 2017

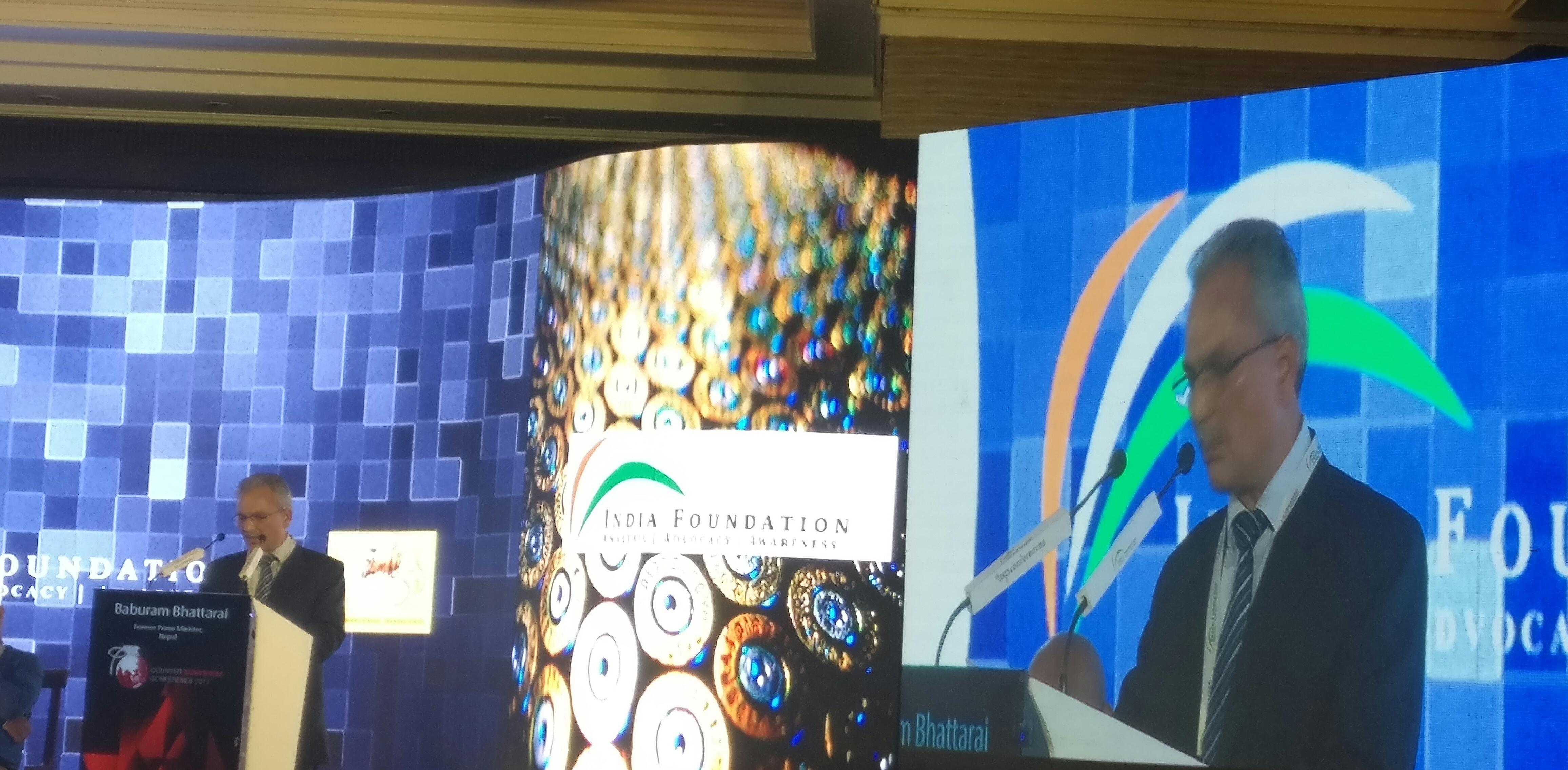

Address by Former Prime Minister Dr. Baburam Bhattarai in Counter Terrorism Conference (14-16 March, 2017) New Delhi, India