By Yubaraj Ghimire— That Nepal, like six other South Asian countries, joined the One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative of China formally, may be read differently at home, in India and, to some extent, in the region. While the outcome of the initiative in terms of the spread of rail and road networks, energy projects and connectivity will take years to emerge, Nepal will have to develop closer working relations with China under this agreement.

By Yubaraj Ghimire— That Nepal, like six other South Asian countries, joined the One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative of China formally, may be read differently at home, in India and, to some extent, in the region. While the outcome of the initiative in terms of the spread of rail and road networks, energy projects and connectivity will take years to emerge, Nepal will have to develop closer working relations with China under this agreement.

Apart from being a dialogue partner with the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, Nepal is among the founding members of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Despite some initial hiccups about joining the OBOR initiative formally, given India’s reservation that was quietly conveyed through some ministers in the present government, there was no possibility of Nepal backing out from the commitment it made and reiterated at the highest level over a period of time. “We have conveyed to China that our joining the Belt and Road initiative is not at the cost of Nepal’s relations with India, and its genuine security concerns. And China has appreciated it,” an influential minister in the present cabinet said.

Nepal, in the past few years, has opened up many sectors, which were earlier restricted to the country’s north. The recent joint military exercise with China was just another example. China’s growing interest in Nepal’s hydropower sector, its construction of the country’s international airport in the tourist city of Pokhara — where China has been permitted to open a consulate — and China becoming the largest FDI player in Nepal illustrate the growth of business and diplomatic relations between the two countries over the years.

Nepal’s entry into the Belt and Road initiative, the possibility of the AIIB diluting the clout of the World Bank and IMF — and reducing their influence over policy matters — may have much larger implications on Nepal’s foreign policy, the framework of which was determined in the context of the Cold War. Matters pertaining to the 1950 Treaty of Peace and Friendship, a framework agreement with India, and the associated understanding that Nepal will procure arms exclusively from India — or from outside with India’s knowledge — could be raised afresh in the new context.

The anarchy and visible erosion in the authority of the state could be the product of many factors. But China has scored over its competitors in creating the perception that its endeavours to improve relations with a country will be in full deference to the sovereignty of that country. India and Western democracies that continue to collaborate with the government, political parties and civil society outfits of various hues — some of which clearly take anti-state stands — ostensibly to promote “liberal democracy and its values” are perceived as responsible for the chaos in Nepal.

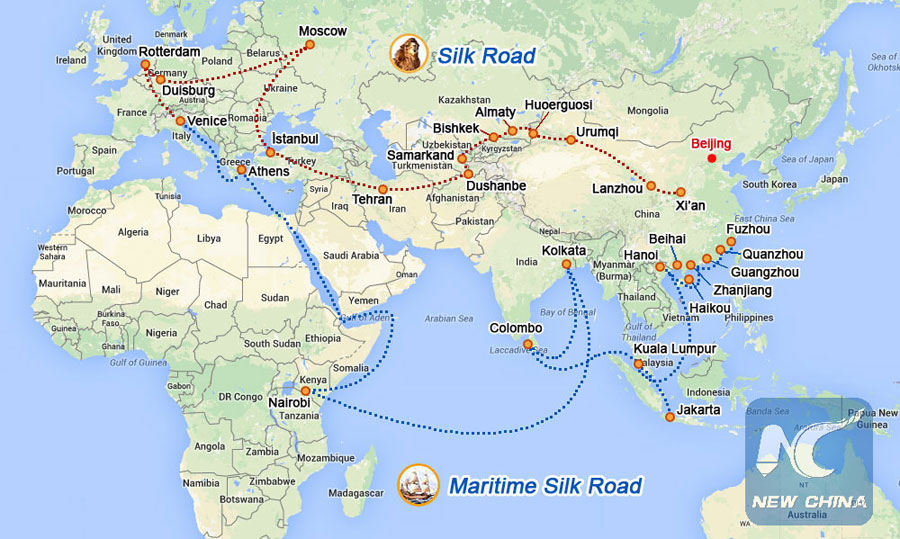

China’s plea that the OBOR is all about connectivity and development with larger ownership and dominant local stakes has enthused Nepal, where the decade-long political experiment and the resultant chaos have hampered the development promised by political parties. If things move in right earnest, China’s role and influence in the new international system may have a much larger visible impact in the region: Nepal seems prepared to welcome that.

In the past, India has not reacted well to Nepal’s proximity to China. In 1988, when Nepal, under King Birendra, imported some arms for the country’s army from China, challenging India’s monopoly, the Rajiv Gandhi government imposed an 18-month economic blockade on the country. India then supported the pro-democracy movement in 1990 that brought the monarchy under a “constitutional framework” in a multi-party system.

In November 2005, the Manmohan Singh government mediated between the “underground” Nepali Maoists and seven political parties bringing them together under an anti-monarchy agenda. This was a response to King Gyanendra’s initiative on according observer status to China in SAARC during the Dhaka summit. Gyanendra also procured a fresh supply of arms and ammunition from China for the Nepal army, still fighting “Maoist insurgents” after India stopped supply in disapproval of the “royal takeover”.

India retaliated by giving up its “twin pillar theory”, abandoning the monarchy that it thought was playing the “China card” all too often. India chose to encourage the Maoists, the Nepali Congress and the Communist Party of Nepal-Unified Marxist Leninist (CPNUML) to opt for a “republic”.

While the constitution (promulgated in September 2015) that India is yet to “welcome” has “institutionalised the republic”, its key proponents — the Maoists and the Nepali Congress, Nepal’s ruling coalition, and the main opposition, the CPNUML, have played a key role in the country joining the OBOR. This time, they are sure that India, which stayed away from the Beijing Forum, will not punish Nepal. China’s stakes and presence in Nepal seem to have been accepted by India as an unstoppable reality.

(This article was originally published in The Indian Express on May 22, 2017. The writer can be contacted at [email protected])