By Shubhajit Roy (26 April 2018) – It was the winter of 1988, when Vijay Gokhale, in his twenties and a fluent Mandarin speaker by then, was the First Secretary (Political) at the Indian Embassy in Beijing and then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi visited China. This was the first visit by an Indian PM in 34 years, after Jawaharlal Nehru in 1954 when Zhao En-lai had announced the Panchsheel, the five principles of peaceful coexistence, which would be derailed by the 1962 war.

With ties strained for three decades, Rajiv’s visit between December 19 and 23, 1988, was the beginning of a thaw. Accompanied by Sonia Gandhi, he met with China’s top leaders, climbed the Great Wall, and attended official banquets where “exquisitely carved vegetable decorations were in the shape of a dragon, symbolizing China, peacock, symbolizing India, and two doves, symbolizing peace”, as Bertil Lintner writes in China’s India War —Collision Course on the Roof of the World.

The exchange between Rajiv and Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping on December 21, 1988, in the Great Hall of the People, in front of the media, was a landmark. Deng welcomed Rajiv as “my young friend” and said: “Starting with your visit, we will restore our relations as friends. We will be friends between the leaders of the two countries. The countries will become friends. The people will become friends. Do you agree with me?” He continued: “So in 1954, when your grandfather, the late prime minister Nehru, visited China, I was also one of the leaders in China. I was vice-premier at that time. At that time, the relations between our two countries were very good.”

Rajiv replied, “Yes. We have been through a few difficulties in between. I hope we can bring things back and get over these difficulties.” To which Deng said, “So this is our common wish. In the considerable period of time in between, there was unpleasantness at each other. Let’s forget it. We should look forward.”

As Rajiv concluded, “There’s so much work to do in both countries,” Deng said, “The genuine start of the improvement of our relations is your visit.”

India and China decided to develop bilateral relations in all spheres as well as work towards resolving the boundary dispute, with a commitment not to use violence and change the status quo along the boundary. The Indian side also affirmed that India considered Tibet an integral part of China and no anti-China activities were permitted on Indian soil (Encyclopaedia of India-China cultural contacts).

As Rajiv returned after meetings with top Chinese leaders including premier Li Peng, the Opposition in India described it as “another glamorous tour” and the “accord” with China as a gambit ahead of Lok Sabha polls; V P Singh called it a “sellout to Beijing”. (Executive Intelligence Review, January 13, 1989).

Between 1962 & 1988

Rajiv’s visit was not the first attempt to mend fences.

In February 1979, then external affairs minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee visited China and identified the border problem as the key obstacle to normalising relations. Li Deng, then vice premier, said, “We should seek common ground while reserving our differences. As for the boundary question, we can solve it through peaceful consultation. This question should not prevent us from improving our relations in other fields.” Foreign minister Huang Hua held three rounds of talks, when Vajpayee referred to China’s support to Naga and Mizo insurgents. He got assurances of such support being stopped, and the five principles of peaceful coexistence were reaffirmed. (Rapprochement across the Himalayas, Keshav Mishra).

The momentum gained from Vajpayee’s visit was stopped after China’s attack on Vietnam while he was still in China. Vajpayee cut short his visit and hurried back home. In the face of public pressure and criticism in Parliament, India denounced the Chinese action as an aggression against Vietnam.

After Indira Gandhi regained power, Chinese premier Hua Guofeng congratulated her. Then, in 1980, Huang Hua attended India’s Republic Day celebrations at the Indian embassy in Beijing, the first Chinese foreign minister to do so in 20 years; he stressed the need for “mutual understanding and cooperation”.

The first PM-level contact after the 1962 war came in May 1980, in Belgrade, where both Indira Gandhi and Hua Guofeng attended the funeral of Yugoslav leader Marshal Tito. They agreed to continue with the process of improving relations. The last meeting at prime ministerial level had been during Zhou Enlai’s visit to India in 1960.

In June 1980, Deng revived Zhou Enlai’s “package proposal” of 1960 by suggesting India and China settle their border dispute on the basis of the existing Line of Actual Control and abandon their respective claims in the eastern and western sectors. This was not acceptable to India, because it sought to legitimise Chinese occupation of territory in the western sector between 1959 and 1962 without offering any territorial compensation to India.

Through the 1980s, India considered rebuilding relations but was cautious. After Indira’s assassination, Chinese premier Zhao Ziyang paid tribute for her efforts to improve relations. “We hope that the two sides will make efforts to keep this momentum going and try to restore the friendly relationship to the level of the 1950s,” he said.

Within a week, new PM Rajiv received vice-premier Yao Yilin on November 4, 1984, and reiterated that his government would continue to follow past policies.

And after the 1988 visit, Rajiv said, “The most important aspect of the trip was establishing direct relationships with China’s leaders”. South Block officials were quoted by EIR as “greatly enhancing India’s diplomatic maneuverability”, since the PM had fashioned a personal equation with both Mikhail Gorbachev and George Bush, and “China was the missing link”. In fact, Gorbachev had visited India a month before and urged Rajiv to build bridges with the Chinese leadership.

After Rajiv

The next leap came with P V Narasimha Rao’s visit in September 1993, when China and India signed an agreement on maintaining peace and tranquillity along the Line of Actual Control. The term “line of actual control (LAC)” appeared for the first time in an official document signed between the two countries.

While status quo was maintained on the border, a decade later Vajpayee went on a six-day official visit in June 2003. The two sides signed a declaration, the first official document in which India recognised the legitimacy of Tibet as Chinese territory.

And, then Vajpayee made a surprise offer to the premier Wen Jiabao to appoint special representatives for border talks and named National Security Adviser Brajesh Mishra as the Indian interlocutor — he had once shaken hands with a smiling Mao in 1970; the only positive overture made by Mao after the war — and a deal was struck on border talks.

Manmohan Singh carried forward the relationship, with two visits in 2008 and 2013. The first visit gave the relationship an intellectual heft and a wider context as the two sides signed a “Shared vision for the 21st century”. Singh maintained through his term that there is “enough space in the world for both India and China to compete and cooperate”.

Although China agreed on a Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) waiver to India after the US leveraged its relationship and George W Bush made a phone call to Hu Jintao, the relationship was not without strains — the Depsang incident in April 2013 was a case in point. That led to the Border Defence Cooperation pact between the two sides.

Baggage of history

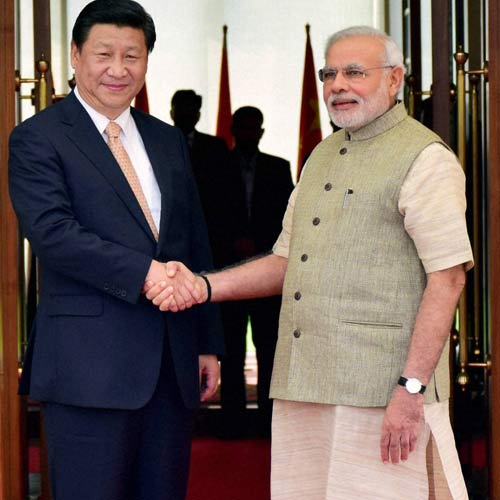

Part of this history will be at play again when Prime Minister Narendra Modi lands in Wuhan Thursday night for an “informal summit” with Chinese President Xi Jinping — who is more powerful than during their previous meetings owing to a constitutional amendment that removed his term limit.

Like Rajiv, Modi too faces an election next year. And like Rajiv, who had diplomatically resolved the Sumdorong Chu stand-off in mid-1987, Modi too had been able to resolve the two-and-a-half-month-long Doklam border stand-off through diplomatic negotiations.

In fact, within a week of the border standoff being resolved in Xiamen, when Xi and Modi met, the two leaders were of the view that they should not let “differences become disputes”. This template was first articulated after their meeting in Astana last year, on the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit.

Modi, who had dealt with the Chinese state-run business in his years as chief minister of Gujarat, had faced the challenge of dealing with the Chinese state in the very first six months of his becoming prime minister.

As he and Xi walked along the banks of the Sabarmati in September 2014, the Chumar standoff was alive, and this was possibly the first time the new Indian leader was facing the challenge of dealing with Beijing. Days before Xi’s visit, Modi had, after all, talked about the “medieval expansionist mindset” in Japan.

Though Modi has visited China thrice, and has met Xi at least 10 times, India’s friction points with China have increased over the last few years.

While China has been blocking India’s membership in the NSG for the last two years, it has not yielded on its opposition to Jaish-e-Mohammad chief Masood Azhar being listed as a global terrorist at the UN. Add to that, the Xi’s Belt and Road Intitiative and India’s opposition to the project on account of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor violating India’s territorial sovereignty.

In a sense, the compact that was made between Rajiv and the Chinese leadership in 1988 has frayed. Three decades later, Gokhale, now a foreign secretary who has served in Beijing, Hong Kong and Taiwan and come to be known as an East Asia specialist, will have to help Modi navigate the new contours of the relationship and move towards a new equilibrium.

Bertil Lintner writes in China’s India War: “There is indeed a ‘New Great Game’ founded on historic mistrust and current competition”. “It has to do with border disputes in the Himalayas, the competition for influence in Nepal, Bhutan, and Myanmar, cross-border insurgencies, the sharing of water resources, and strategic rivalries in the Indian Ocean.”

And this time, Lintner says, “it is not between Imperial Russia and the British Empire, but, after a long, complicated, and often violent history, between and independent India and China, a communist-ruled country that has risen from famine, chaos and anarchy to become the world’s new economic superpower”.

[email protected]. This report first appeared in The Indian Express.