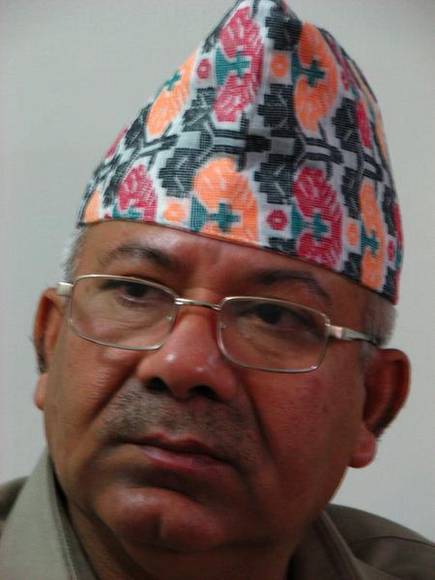

Vijaya Prashad (9 March 2020) – FOR more than 50 years, Madhav Nepal has been involved in his country’s communist movement. He first joined the movement in 1966 as a student and has since been the leader of several communist parties, has been the Prime Minister of Nepal, and is now one of the key leaders of Communist Party of Nepal (CPN). It was “exploitation in Nepalese society, the poverty”, he told me recently, that drew him into the communist movement; only later did he read Marxist books and Soviet novels. “Only the communist party,” he said, “can hope to solve Nepal’s problems.” This is an attitude that remains with him, though he is now far away from his days in the peasant uprising of 1969, known as the Jhapa movement, and his early attachment to Indian naxalism. Madhav Nepal is now, easily, the revered figure in Nepali communism.

In May 2018, Madhav Nepal, along with his old friends K.P. Oli and Prachanda, brought most of the communist groups together to form the CPN. The two largest groups in the party won a two-thirds majority in the elections to the parliament and to the seven provincial Assemblies; they had contested these elections on a unified platform after years of rancour. It was after these elections that the various groups in Nepal decided that people wanted them to unify despite their own differences of political sensibility. Between them, Oli, Madhav Nepal and Prachanda share decades of common struggle and personal animosity. They come from the same movement, although Prachanda had taken the Maoists into armed struggle for a decade from 1996. “I tried my best to persuade their leaders to stop the armed struggle and to come into the political system,” Madhav Nepal said, but they were inspired by Shining Path in Peru and other such movements, which, after much useless bloodshed, collapsed. Eventually, with a great deal of persuasion, the armed struggle ended, and a decade-long process led to the new unified party.

At a meeting of the leadership of his party in the late 1980s, there was no anticipation that the monarchy would collapse or even that a constitutional monarchy would be possible. After the Jana Andolan, or People’s Movement, of 1990, the political parties snatched power from King Birendra and created a constitutional monarchy; still, at a meeting shortly afterwards, Madhav Nepal recalled, none of his comrades could imagine an easy removal of the King. Nor could Madhav Nepal imagine then that he would become Prime Minister or that his party would command an absolute majority in all the elected bodies. But this is what happened, after the royal massacre in 2001 carried out by Crown Prince Dipendra and the short-lived rule of the autocratic King Gyanendra. The monarchy collapsed, and the main political parties, the Nepali Congress and the Communists, took charge. Over the years, the Nepali Congress became less and less the powerful party it was, largely because it was unable to tackle the exact condition that brought Madhav Nepal into politics in the 1960s: Nepal’s great poverty.

Those who collect data have for a long time said that one in four Nepalis lives in extreme poverty and that the country is one of the poorest in the world. High child mortality due to poor health care and terrible hunger due to high food prices and low wages keep the people in a profound state of impoverishment. There is a desire to move Nepal away from its Least Developed Status by 2022. The Communists are eager to lift the per capita income from $862 a year to $5,000 a year. This will require investment in education and health and a dramatic improvement in the employment situation in the country. This vision is what unites all the Communists.

The programme of the Communist government has been fairly straightforward, even modest. It is hard for a modern party to disagree with an agenda that includes an end to corruption, a more efficient use of tax money, fiscal federalism (shifting 50 per cent of resources to provinces and municipalities), and more emphasis on organic agriculture and on non-fossil fuel energy (mainly hydropower). Dependence on India’s transportation system for its trade has forced Nepal into a conflicted relationship with its main neighbour; India has used this advantage in a rather disgraceful way, closing the borders when it has wanted to put pressure on Nepal. The Nepali government has looked for ways to reduce its economic dependence on India, including by encouraging China to build a railroad and a roadway from Tibet to Nepal. This is less a tilt towards China, which is what many people see it as, and more an attempt to balance Nepal’s position between two large countries.

Controversy over the MCC

The issue of hydropower is now at the centre of a controversy in Nepal. The United States government offered Nepal—through the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC)—$500 million towards the building of transmission lines and roadways. This is a considerable amount of money, which Nepal does not otherwise have access to. If these lines and roads are built, it will improve the country’s infrastructure and enhance its economy.

Nothing is as easy as it seems. The MCC is not an innocent pathway for funds. Madhav Nepal tells me that he is very concerned about this money and its implications. At a recent Standing Committee meeting of the CPN, the leadership was divided over these funds. Some people felt that the money was merely for development and should be accepted without any concern. What they would like to do is ratify the MCC’s Nepal Compact in the parliament even if there is a whiff of suspicion that the Compact overrides Nepal’s sovereignty. They think that the money is worth it.

Madhav Nepal points to the Indo-Pacific Strategy Report, which the U.S. government released in June 2019. It openly talks about drawing in Asian countries to undermine China’s Belt and Road Initiative project and China in general. The report describes China as a “revisionist power” and frankly states that the new Indo-Pacific Strategy is designed to constrain China. The CPN, which has close ties to Beijing, has been quite clear that it will not join the Indo-Pacific Strategy. There is no disagreement here.

Those who want to sign the MCC and take the $500 million say that there is no connection between the MCC and the strategy. However, in November 2019, the U.S. government released a second report (A Free and Open Indo-Pacific: Advancing a Shared Vision) that talked about the MCC as being part of its overall goal in Asia. The MCC, it says, is one of many “new and innovative mechanisms to improve market access and level the playing field for U.S. businesses” in Asia; it is also a means to draw countries like Nepal into the general orientation of U.S. foreign policy. This report, which directly links the MCC to the Indo-Pacific Strategy, deepened the controversy in Nepal.

“The Indo-Pacific Strategy cannot be supported,” Madhav Nepal told me. “We are clear on that. If any such thing is linked to the MCC, we cannot accept the MCC.” The U.S., he says, told him directly that there was no link between the MCC and the Indo-Pacific Strategy and that no military alliance was being proposed here. The U.S. Ambassador, Madhav Nepal says, “came to make this clear”. Madhav Nepal asked him for a written commitment; this has not come yet.

I asked Madhav Nepal what the country would do to build the transmission lines and the roads if it did not take the $500 million from the U.S. “We will go to the Asian Development Bank,” he said. Of course, both Japan and the U.S. dominate this bank, which might be pressured not to lend Nepal the money.

Uranium

In 2014, Nepal’s Department of Mines and Geology found a large deposit of uranium in the Upper Mustang region, a remote area that is part of the old Kingdom of Lo and is right on Nepal’s northern border with China. A 2017 report from Nepal’s Ministry of Industry noted that the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) found the uranium to be of the “highest grade”. Giriraj Mani Pokharel, the Minister of Education, Science and Technology, told an IAEA conference in December 2018 that the “country’s prosperity cannot be achieved without its development”. Nuclear materials are now key to Nepal. But the uranium sits near the glaciers that feed the Kali Gandaki river. Any mining there will certainly pollute the river. This is a concern for environmentalists. Amendments made to the Safe and Peaceful Use of Nuclear and Radioactive Materials Bill in the Nepali parliament raise some of these questions.

Madhav Nepal smiles when I ask him whether this nuclear deposit will give Nepal leverage against the U.S., India and China. There is nothing for him to say here. It is obvious that each of these countries would like to have access to the Mustang deposits and that here is the resource that could finance Nepal’s development (at what environmental cost will have to be seen). The tussle over Mustang is going to exacerbate the rivalry between the U.S. and India on one side and China on the other. It will take considerable skill for the Nepali communists to manage this situation.

“Nepal is a small country,” Madhav Nepal says. “We would not like to be dragged into any controversy.” This is a sensible statement from a man who has spent his entire life fighting to improve the condition of his people. As far back as 1989, when Madhav Nepal met the Nepali Congress leader G.P. Koirala to find out whether the communists and the Congress could jointly fight against the monarchy, Koirala gave him a warning. Yes, he said, we can conduct united actions but “keep [it] secret otherwise the Americans will know”.

This article first appeared in FRONTLINE.