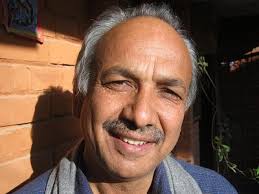

By Yubaraj Ghimire (May 29, 2017) – Several parallel and contradictory trends are clearly visible in Nepal’s politics, an area which has been a victim of a prolonged transition process and the resultant adhoc-ism over the years. Pushpa Kamal Dahal “Prachanda”, chairman of the Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist Centre, on Wednesday claimed that his resignation on the “successful completion” of the first phase of the local-level election, and in deference to his earlier commitment with the Nepali Congress, his coalition partner, amounts to injecting a “moral component, something long absent” from Nepali politics.

His act, partly in deference to his commitment, and partly tactical, with an eye to reap rich political dividends in the future, has earned him some positive mileage for now as a trustworthy politician. However, he will be judged more appropriately by how he conducts himself in the days and years to come. So far, Dahal’s personality consists of a mix of contradictory traits: A revolutionary in the past, a quiet “dealer” with domestic and external actors, a power-hungry politician and someone lacking consistency in his approaches.

If he sticks to the alliance with the current partner Nepali Congress into the future as well, and accepts the role of a junior partner in the coalition in a hung parliament, that will be the first proof of his having become honestly pragmatic.

That will, however, only be known in the coming week as the country is in the midst of an exercise to have a new prime minister elected through parliamentary majority, although there are signs of hurdles coming in the way, given the ongoing obstruction of parliament itself. Sher Bahadur Deuba, chairman of the Nepali Congress, is the joint candidate of the current coalition, but the Maoists, going by their past record, may insist on shares disproportionate to their size.

Nepal has set up a notorious record in establishing (un)parliamentary precedents over the transition period, dictated largely by the interests of a few leaders and their captive parties as well as parliament. President Bidhya Devi Bhandari unveiled government programmes and polices a day after Dahal had resigned, reducing the government to caretaker status, with the successor likely to take at least a week to emerge formally, provided that the opposition lifted the obstruction. Nepal’s constitution requires that only a parliament “in order” elects from the floor its leaders, preferably by consensus, failing which “a majority” becomes the deciding factor.

But Nepal’s politics has largely been about quiet deals between the parties in power and the opposition. And of late, it has also been about muscle-flexing and derailing the constitutional process and parliamentary sanctity. The main opposition — the Communist Party of Nepal-Unified Marxist Leninist — temporarily lifted the obstruction of the House to enable President Bhandari to read out the policy and programmes, possibly considering the fact that she belonged to the UML prior to her becoming head of the state, under a “quota”-based agreement among the key political parties.

Dahal, who initially wanted to announce his resignation after a speech in parliament last week, chose to do it through a nationally televised address as the opposition obstruction deprived him of the parliamentary forum. But a new leader or prime minister can only be elected by a parliament in order. What if the UML continues with its muscle-flexing? The UML and the current ruling coalition clash on many issues, including on conducting the second phase of local-level elections scheduled on June 14.

The UML, backed by the supreme court order, is opposed to any additional local bodies being created in four provinces slated for the second round of elections, something that the Dahal government decided on the eve of its departure, in order to “accommodate” Madhes-centric parties that had boycotted the polls during the first round.

“But we cannot hold the poll as planned if these alterations are to be made in the number,” an election commissioner says. The Madhes-centric Rashtriya Janata Party promptly announced obstructing the second phase of the polls in protest. A boycott, or disruption of the second phase of the poll, will not only be a setback to what Dahal claimed credit for, but will also bring the legitimacy of the election held in 283 local bodies in the phase, into question.

India, that had only “noted” but not “welcomed” the controversial, and apparently inadequate constitution promulgated so far, exhibited a slightly changed posture this time around as Prime Minister Narendra Modi congratulated Dahal over the “successful conduct” of the local bodies poll. But with the legitimacy as well as the possibility of the poll mired in doubts, the main opposition blocking parliament, and the judiciary and parliament plus executive pitched in open battle, the state is not only appearing weaker, but may turn dysfunctional.

In short, there is no solution visible within the framework of the current constitution, but whether the muscle-flexing key parties will involve all other forces in giving the constitution an acceptable shape and size, is doubtful, given their rigid stance all along.

(This article was originally published in The Indian Express on May 29, 2017)