By Mridu Iyer/Jivesh Jha–

By Mridu Iyer/Jivesh Jha–

Dehradun

Seeking to provide more teeth to the existing International Laws, the member states of South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) have introduced fair corpus of clauses of the international conventions in their Fundamental Rights (FR) section to present their Constitution in sync with the international treaties and conventions to which they are state parties.

The Constitution of any country is regarded as a living document and a robust device which makes the government system work. It lays down the framework defining the structure, procedure and powers of the government institutions and sets out FR, Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) and fundamental duties of every citizen. “As the supreme law of the land, the Constitutions of SAARC states should acknowledge the international laws and respond to the challenges of its non-compliance,” said Dr Nidhi Saxena, faculty of International Law at Central University of Sikkim.

Having gone through the provisions of International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), it became clear that these sovereign nations are pledged to acknowledge the conventions and treaties in their domestic legislations. These democratic countries are at even to envisage that their respective constitution is supreme law and it’s enacted for garnering the principles of democracy and socialism.

The ICCPR was adopted by United Nation (UN)’s General Assembly on December 19, 1966 and it came into force on March 23, 1976. There are currently 74 signatories and 168 parties to the ICCPR. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and ICCPR and its two Optional Protocols are collectively known as International Bill of Rights.

The preamble of these international instruments sets out the objective of recognizing the inherent dignity of each individual and undertakes to promote conditions within states to allow the enjoyment of civil and political rights without any hassle.

Article 2 (2) of Part II imposes an obligation on each state party to ICCPR to take the necessary steps, ‘in accordance with its constitutional processes and with the provisions of the present Covenant, to adopt such laws or other measures as may be necessary to give effect to the rights recognized in the present Covenant.’

Even as the Constitutions of SAARC nations assert that they are pledged to quicken the pulse of international instruments for proper functioning of their democratic norms, they are quick to declare that every right incorporated under the major conventions cannot to be ensured to every person in the similar fashion.

A look at what has constrained and qualified that right, by way of law, religion and politics in South Asia.

The Indian Constitution, the eldest charter in the region, provides that right to life and liberty shall be inviolable. Article 21 of the Constitution which does not employ the expression ‘state’ allows the scrutiny of private actions that violate right to life and personal liberty. The mandate of Article 21 is to forbid the denial of life and liberty, except according to the procedure established by law is applicable against all entities whether state or private. Moreover, Article 21 avows that every right to live a dignified life would be fundamental rights. The said arrangement is of intrinsic value as it shows a deep commitment of state towards all the natural rights.

Noted, right to life and liberty is available to not only citizens but also to every person [i.e., non-citizen] respiring on the India soil. The said arrangement is in consonance with Article 6(1) and 9(1) of ICCPR. Meanwhile, similar arrangement has been ensured under Article 32 of Bangladeshi Constitution. Similarly, Article 14 of Pakistani charter beginning with the marginal note of ‘Inviolability of dignity of man, etc.’ provides that the dignity of man and, subject to law, the privacy of home, shall be inviolable.

“All persons shall have the right to life, liberty and security of person and shall not be deprived of such rights except in accordance with the due process of law,” reads Article 7(1) of Bhutanese Constitution.

Unlike Bhutanese statute, Article 21 of the Indian Constitution is worded with ‘procedure established by law’ and the provision reads, “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procure established by law.”

In the case of Sunil Batra Versus Delhi administration (AIR 1978), the honorable Supreme Court was of the opinion that the expression “procedure established by law” meant the same thing as the phrase “due process of law” used in the American Constitution. “Truly our constitution has no ‘due process clause’ as the VIII amendment (of the American Constitution) but in this branch of law, after Maneka Gandhi’s case the consequence is the same,” observed much-admired Justice Krishna Iyer while pronouncing the judgment of Sunil Batra’s case.

Further, “the mere prescription of some kind of procedure is not enough to comply with the mandate of Article 21. The procedure prescribed by law has to be fair, just and reasonable not fanciful, oppressive or arbitrary; otherwise, it should not be on procedure at all and all the requirement of Article 21 would not be satisfied. What is fair or just? A procedure to be fair or just must embody the principles of natural justice. Natural justice is intended to invest law with fairness and to secure justice,” the highest court of land in India held while dispensing the landmark case of Maneka Gandhi Versus Union of India (AIR 1978). The Court stressed on the need of observing law as reasonable laws, ‘not mere an enacted piece of law.’

Now it is submitted on all fronts that the Indian legal system has imported the American concept of ‘due process of law’ into Indian Constitution.

In the similar vein, the Maldivian, Nepali, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Afghani charter also incorporate right to life and liberty under Article 21, Article 16, Article 14, Article 32 and Article 24, respectively. But the statutes lack the expression “procure established by law” or “due process of law.”

“With the incorporation of the expression ‘procedure established by law’ or ‘due process of law’ the rights of persons are protected to an extent,” opined Dr Saxena. She maintained that the substantial justice would always remain in question in absence of the phraseology of ‘due process of law’ or ‘procedure established by law.’ “It appears that the south Asian states, save for India and Bhutan, are little serious in acknowledging natural justice. The insertion of the phrase ‘due process of law’, of course, irrigates universal justice.”

“When men are pure, laws are useless; when men are corrupt, laws are broken,” added Dr Saxena while paraphrasing philosopher Benjamin Disraeli. “With ensuring no space for ‘due process of law’, the legislatures of SAARC states, save for India and Bhutan, have attempted their best to rub salt over the raw wounds caused on justice seekers.”

On a separate context, the provision in one way or the other clarifies that right to privacy is implicitly sheltered within the spirit of right to life and liberty.

However, Article 16(c) (6) read with Article 21 provides that right to life and liberty can be curtailed in Maldives in order to protect the tenets of Islam. The clause may impact on the rights of persons and may be used as justification to uphold legislation which currently appears to be discriminatory towards the persons following other religious faiths.

Standing on a different footing, the Sri Lankan constitution lacks any express provision relating to life and liberty.

On the other hand, the south Asian states are at even to envisage that all persons are equal before the law and are entitled to equal and effective protection of the law. The cornerstone has been set by Article 14(1) of the ICCPR and Article 14, Article 18, Article 7(15), Article 12, Article 22, Article 25, Article 20, and Article 27 of Indian, Nepali, Bhutanese, Sri Lankan, Afghani, Pakistani, Maldivian, and Bangladeshi Constitutions, respectively.

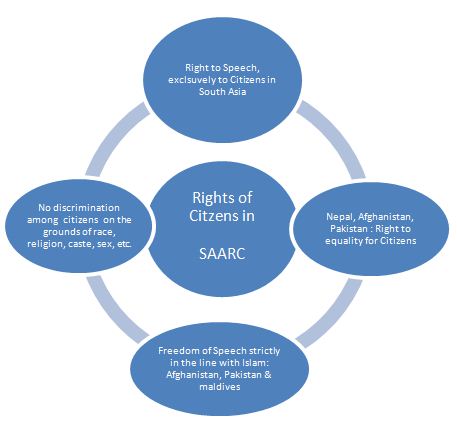

However, the Constitution of Nepal, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh provides right to equality exclusively to their citizens, while the same right is available to citizen as well as non-citizen in India, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, and Maldives.

Noted, ICCPR enacts that right to equality should be available to citizen and non-citizen both.

In contrast, the South Asian Constitutions envisage that every citizen has right to express one’s own convictions and opinions. Even as the ICCPR under Article 19 (1) offers freedom of speech and expression to every person, the South Asian states provide this right exclusively to their citizen. The charters offer a blanket power to their citizen to freely propagate their ideas by words of mouth, writing, painting, pictures or any other mode.

Unlike others, “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought and the freedom to communicate opinions and expression in a manner that is not contrary to any tenet of Islam,” says Article 27 of Maldivian Constitution beginning with a marginal note of “Freedom of expression.”

Its been a well-settled law that innocence will be the original state. The Constitutions unanimously legislate that the accused ‘shall’ be innocent until proven guilty by the order of a competent court of law.

Standing on the same page, the Constitutions collectively provide right to ‘protection in respect of conviction for offences’ to every person—whether citizen or non-citizen– on whom its been alleged that he has committed any offence. According to acclaimed jurist Austin, a crime is an act or omission which law punishes. So, in eyes of criminal jurisprudence of South Asia, the exercise of criminal jurisdiction depends upon the locality of the offences committed, and not upon the nationality or locality of the offender.

The Indian charter under Article 20 (1) provides protection against ex post facto laws. An ex-post facto law is a law which imposes penalties retrospectively. The provision prohibits the competent legislature to make retrospective criminal laws.

Similarly, Article 20(2) embodies protection against double jeopardy. The provision clarifies that no person shall be prosecuted and punished more than once for the same offence. The clause acknowledges the common law rule of “Nemo dabet vis vexari,” which means that no man should be put twice in peril for the same offence.

Furthermore, Article 20(3) envisions prohibition against self-incrimination. The provision recognizes the general principle of English and American jurisprudence that no one shall be compelled to give testimony which may expose him to prosecution for crime. In general, the Article provides that no person accused of any offence shall be compelled to be a witness against himself.

On the other hand, Article 20, Article 7(16), Article 13, Article 25, Article 12 & 13, Article 59 & 60, and Article 35 of Constitution of Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Maldives and Bangladesh are in consonance with Article 20 of the Indian Constitution, the largest constitutional document of the globe.

However, Article 15(1) [Ex Post facto law], Article 14(7) [Double jeopardy], and Article 14(3)(g) [Prohibition against self-incrimination] of ICCPR lays down the similar criminal jurisprudence.

Akin to Article 9(2)-(4) of the ICCPR, the South Asian states envisage that the “Every person who is arrested shall be produced before a judicial authority within a period of twenty-four hours after such arrest, excluding the time necessary for the journey from the time and place of arrest to such authority, and the arrested person shall not be detained in custody beyond the said period except on the order of such authority,” reads Article 20(3) of Nepal Constitution. Every person undergoing trial shall have the right to be informed about the proceedings of the trial,” says Article 20(8) of the same statute. The similar arrangement has been provided under Article 22 (India) , Article 33 (Bangladesh), Article 7(20) [Bhutan], Article 13 (Sri Lanka), Article 31 (Afghanistan), Article 10 (Pakistan), and Article 48 (Maldives).

On the contrary, though Article 25 (c) of ICCPR advocates for the equality of opportunity for all the persons irrespective of their nationality, the constitutions are not at odds in ensuring the said right exclusively to their citizens.

Although the provisions contained under Article 19, 21 and 22 of ICCPR provides right to freedom of speech and expression, assemble peacefully, forming associations, move freely, reside and settle and practicing any profession to all persons, the same has been exclusively availed to the citizens in South Asia.

Explaining that the discrimination on any ground is not acceptable in a civilized world, these developing states are at the same platform to envisage, “The State shall not discriminate against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race caste, sex or place of birth.”

However, the Constitution of Bhutan asserts that the state shall not discriminate any ‘person’ on any ground while the remaining member states of SAARC enact the analogous provision exclusively for ‘citizens’.

Nonetheless, Article 26 of ICCPR reads as, “All persons are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to the equal protection of the law. In this respect, the law shall prohibit any discrimination and guarantee to all persons equal and effective protection against discrimination on any ground such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.”

What are those qualifiers?

The Constitutions of SAARC states assert that there should not be a narrow interpretation of fundamental rights, but that does not mean that there cannot be any constriction.

No doubt, the South Asian states incorporate the provisions of ICCPR in one way or the other. However, the complete acknowledgement of the Convention is a still a tall task.

- Religion

The Islamic states—Afghanistan, Maldives, and Pakistan—have asserted that freedom of speech and expression is subject to any reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the interest of glory of Islam. “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought and the freedom to communicate opinions and expression in a manner that is not contrary to any tenets of Islam,” reads Article 27 of Maldivian Constitution. The similar restrictions have been provisioned in the charters of Afghanistan and Pakistan under Article 3 and 19, respectively.

On the other hand, even as Pakistani Constitution envisages that there would not be any form of inequality, they are yet to ensure no room for disparity at legislative spectrum. Article 41(2) provisions that a person shall not be qualified to contest the Presidential election unless he is a Muslim. However, the Article 41(2) appears to be conflicting with Article 27 as the latter ruled out fundamental axes of social inequality.

“No citizen otherwise qualified for appointment in the service of Pakistan shall be discriminated against in respect of any such appointment on the ground only of race, religion, caste, sex, residence, or place of birth,” reads Article 27 of Pakistani Constitution beginning with a marginal note of “Safeguard against discrimination in services.”

Like Pakistan, the Afghani statute envisions that one must be Muslim, born of Afghan parents and shall not be a citizen of another country, for becoming a President,’ Article 62.

Moving a step ahead than Afghanistan and Pakistan, the Maldivian charter provisions that one must be a Sunni Muslim, born to parents who are Maldivian citizen and who is not also citizen of a foreign country, to run for Presidential election,’ Article 109. The similar qualification has been envisaged for Vice President,’ Article 122 (c). Moreover, the essential qualification for judges (A-149), Member of Parliament (A-73 read with A-130), and among other vital posts stand on a similar footing with Presidential qualification.

Meanwhile, a non-Muslim may not become a citizen of Maldives,’ says Article 9(d) of Maldivian charter.

- National Sovereignty and integrity

The Constitutions unanimously believe that ‘interests of sovereignty and integrity, the security of state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court, or harmonious relations, defamation or incitement to an offence’ will be paramount and freedom of speech will not be unconditional. Similarly, the statutes forbid any acts jeopardizing the national sovereignty and integrity of the nation.

- Only for citizens

The Constitutions of SAARC states provide some of the FRs exclusively to their citizen. The fundamental documents have unanimously laid down a broader canvas for the FR but with “reasonable” restrictions.

Marrying with a foreign national could cost you dearly if you have an ambition to represent the people of Bhutan. The charter bars a person who have developed courtship with a foreign national to contest any election, Article 23 (4)(a). The arrangement is supported by Section 179 (f) of Election Act of Kingdom of Bhutan, 2008 as well.

Similarly, the Nepali charter also bars a non-Nepali national, married with a Nepali person, to hold any vital government offices, Article 289. This provision has potential to put the rights of women, who are non-Nepali, beneath the civil and political status.

The persons who have solemnized marital bonding with a non-Nepali national remained deeply offended after sensing that their husband or wife or their issues will be beneath the civil and political status. While talking about the most disputed provision, the bushel has been set by Article 289 which bars a naturalized citizen to hold any of the legislative, judicial and constitutional posts. The provision clarifies that the naturalized citizens are inferior to descent citizens. However, Article 18 still mirrors right to equality and equal protection before law.

When asked what led the South Asian countries to ensure right to freedom of speech and expression exclusively to citizens, faculty of international Law at HNB Garhwal Central University, Alok Kumar Yadav, said, “The freedom of speech and expression is one of the major fundamental rights (FR) in democratic countries. And, its beyond any iota of doubt that the freedom of opinion and expression is an ornament of democracy. As its one of the major FR, it cannot be made available to a non-citizen. In absence of a broader understanding, a non-citizen might lose his balance while commenting on national policies and his comment might have potential to jeopardize the harmony in society. However, some other rights like right to life and liberty, or right to criminal justice and equal protection before law should be given to a non-citizen as well.”

Expressing a differing view, political commentator Anurag Acharya, who is also associated with ‘Nepali Times’ newspaper in Kathmandu argued that the freedom of speech and expression cannot be limited to citizens, it has to be in consonance with international laws. “If our domestic laws and constitutional provisions are against international standards, they need to be amended. If they are not then as a signatory state, we stand in violation.”

He then went on to argue that the Constitutional provisions relating to freedom of speech embraced under South Asian Constitutions are not compatible with ICCPR.

Showing satisfaction with political analyst Acharya, an eminent media expert Laxman D. Pant said, “Some commitments to international community are limited on papers.”

When asked whether Nepali laws irrigate the right of free speech, Mr. Pant, who also delivers lecture on Journalism in Kathmandu University, said, “Nepal’s law guarantees right to freedom of expression. There are about a dozen of specific laws protecting media freedom with some reasonable restrictions. However, the implementation of such legislations is still an uphill task.”

Noted, Article 18 (1) of ICCPR says, “Everyone shall have the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.” In the similar breath, Article 19(1) of the same Convention asserts with all words that, “Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.”

The SAARC states are signatories of this Convention.

Meanwhile, the statutes unanimously mention that the right to information falls within the ambit of right to speech and expression.

- Challenges:

There is no legal status of international conventions in the domestic legal systems of SAARC states unless its been ratified by the parliament. However, the charters stand on the same stage to command that any conventions reached at international fronts shall straightaway be declared void if they are inconsistent with the fundamental document of their country.

“Unlike international laws, those who violate domestic law receives a punishment deemed fit by a court of law,” said Abhiranjan Dixit, a faculty of International law at Uttaranchal University, Dehradun, adding, “It’s been a tough task in South Asia to acknowledge the international human rights laws in letter & spirit and punish them who are found violating international laws.”

However, “the Indian constitution has succeeded enough to ensure natural rights, often called divine rights, to a non-citizen as well; since, the rights given by the almighty cannot be curtailed at any pretext by an authority. For instance, rights to equality, right to life & liberty, or right to fair trial have been made available to a non-citizen as well.”

The South Asian nations should consolidate their efforts and focus their energies on existing laws rather than making further newer laws, unfamiliar to our society, culture and harsh realities of the ordinary life. “As the states of SAARC are sovereign, they are free to script laws favorable to their situations,” further added professor Yadav.

The commentators often say, “The only thing universal about human rights is their universal violation.”

Instead of paying mere lip service, “the South Asian countries should draw an inspiration from ICCPR and revamp their vows in actualizing the venerated vision for all humanity,” further added Dr Saxena.

However, no police station, Human Rights Commission, Courts, academicians, social activists, or lawyers can scrutinize every nook and corner of any country to prevent human rights’ maltreatment—it is ultimately for the citizen of any country to treat each other equals without any hassle.

Published on: October 9, 2016

The authors can be reached at [email protected] & [email protected]

(Ms. Iyer holds LL.M (Constitutional Law) from IMS Unison University and Mr. Jha is a contributing writer for NFA)