By Gordon Corera (Security correspondent, BBC) – Russia’s leader Vladimir Putin is trapped in a closed world of his own making, Western spies believe. And that worries them.

For years they have sought to get inside Mr Putin’s mind, to better understand his intentions.

With Russian troops seemingly bogged down in Ukraine, the need to do so has become all the more necessary as they try to work out how he will react under pressure.

Understanding his state of mind will be vital to avoid escalating the crisis into even more dangerous territory.

There has been speculation that Russia’s leader was ill, but many analysts believe he has actually become isolated and closed off to any alternative views.

His isolation has been evident in pictures of his meetings, such as when he met President Emmanuel Macron. the pair at far ends of a long table. It was also evident in Mr Putin’s meeting with his own national security team on the eve of war.

It had been created, they say, by a tight “conspiratorial cabal” with an emphasis on secrecy. But the result was chaos. Russian military commanders were not ready and some soldiers went over the border without knowing what they were doing.

Single decision maker

Western spies, through sources they will not discuss, knew more about those plans than many inside Russia’s leadership. But now they face a new challenge – understanding what Russia’s leader will do next. And that is not easy.

“The challenge of understanding the Kremlin’s moves is that Putin is the single decision-maker in Moscow,” explains John Sipher, who formerly ran the CIA’s Russia operations. And even though his views are often made clear through public statements knowing how he will act on them is a difficult intelligence challenge.

“It is extremely hard in a system as well protected as Russia to have good intelligence on what’s happening inside the head of the leader especially when so many of his own people do not know what is going on,” Sir John Sawers, a former head of Britain’s MI6, told the BBC.

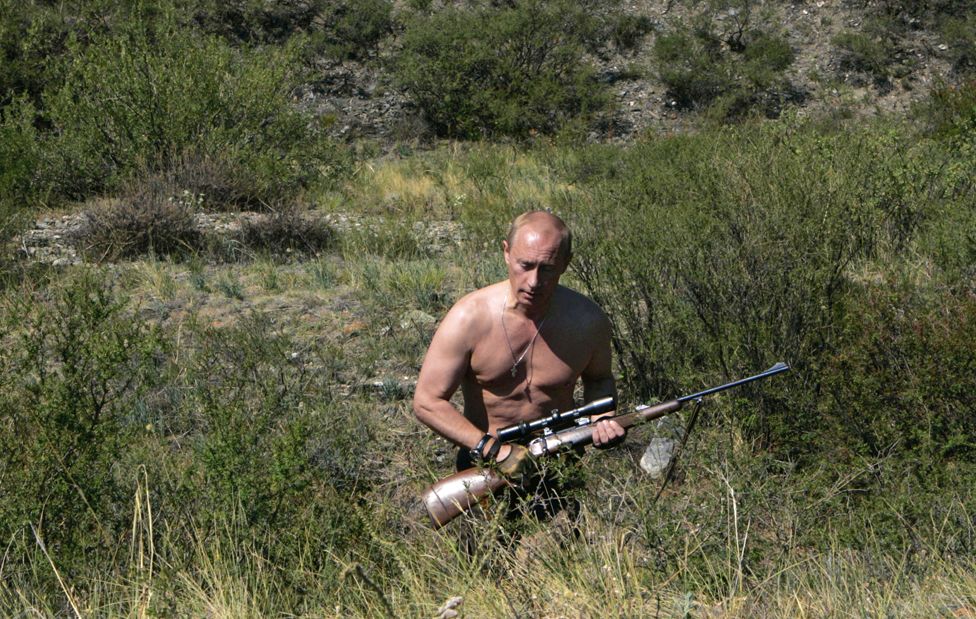

IMAGE SOURCE,SPUTNIK / AFP

IMAGE SOURCE,SPUTNIK / AFPMr Putin, intelligence officials say, is isolated in a bubble of his own making, which very little outside information penetrates, particularly any which might challenge what he thinks.

The circle of those Mr Putin talks to has never been large but when it came to the decision to invade Ukraine, it had narrowed to just a handful of people, Western intelligence officials believe, all of those “true believers” who share Mr Putin’s mindset and obsessions.

The sense of how small his inner circle has become was emphasised when he publicly dressed down the head of his own Foreign Intelligence Service at the national security meeting just before the invasion – a move which seemed to humiliate the official. His speech hours later also revealed a man angry and obsessed with Ukraine and the West.

Those who have observed him say the Russian leader is driven by a desire to overcome the perceived humiliation of Russia in the 1990s along with a conviction that the West is determined to keep Russia down and drive him from power. One person who met Mr Putin remembers his obsession with watching videos of the Col Gaddafi being killed after he was driven from power in 2011.

IMAGE SOURCE,DENIS SINYAKOV

IMAGE SOURCE,DENIS SINYAKOVWhen the director of the CIA, William Burns, was asked to assess Mr Putin’s mental state, he said he had “been stewing in a combustible combination of grievance and ambition for many years” and described his views as having “hardened” and that he was “far more insulated” from other points of view.

Is the Russian president crazy? That is a question many in the West have asked. But few experts consider it helpful. One psychologist with expertise in the area said a mistake was to assume because we cannot understand a decision like invading Ukraine we frame the person who made it as “mad”.

The CIA has a team which carries out “leadership analysis” on foreign decision makers, drawing on a tradition dating back to attempts to understand Hitler. They study background, relationships and health, drawing on secret intelligence.

Another source are read-outs from the those who have had direct contact, such as other leaders. In 2014, Angela Merkel reportedly told President Obama that Mr Putin was living “in another world”. President Macron meanwhile when he sat down with Mr Putin recently, was reported to have found the Russian leader “more rigid, more isolated” compared with previous encounters.

IMAGE SOURCE,ANADOLU AGENCY / GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,ANADOLU AGENCY / GETTY IMAGESDid something change? Some speculate, without much evidence, about possible ill-health or the impact of medication. Others point to psychological factors such as a sense of his own time running out for him to fulfil what he sees as his destiny in protecting Russia or restoring its greatness. The Russian leader has visibly isolated himself from others during the Covid pandemic and this also may have had a psychological impact.

“Putin is likely not mentally ill, nor he has changed, although he is in more of a hurry, and likely more isolated in recent years,” says Ken Dekleva, a former US government physician and diplomat, and currently a senior fellow at the George HW Bush Foundation for US-China Relations.

But a concern now is that reliable information is still not finding its way into Mr Putin’s closed loop. His intelligence services may have been reluctant before the invasion to tell him anything he did not want to hear, offering rosy estimates of how an invasion would go and how Russian troops would be received before the war. And this week one Western official said Mr Putin may still not have the insight into how badly things are going for his own troops that Western intelligence has. That leads to concern about how he might react when confronted with a worsening situation for Russia.

Madman theory

Mr Putin himself tells the story of chasing a rat when he was a boy. When he had driven it into a corner, the rat reacted by attacking him, forcing a young Vladimir to become the one who fled. The question Western policymakers are asking is what if Mr Putin feels cornered now?

“The question really is whether or not he doubles down with greater brutality and escalates in terms of the weapon systems that he’s prepared to use,” said one western official. There have been concerns he could use chemical weapons or even a tactical nuclear weapon.

“The worry is that he does something unbelievably rash in a vicious press-the button way,” says Adrian Furnham.

Mr Putin himself may play up the sense that he is dangerous or even irrational – this is a well-known tactic (often called the “madman” theory) in which someone with access to nuclear weapons tries to get his adversary to back down by convincing them that he may well be crazy enough to use them despite the potential for everyone to perish.

For Western spies and policymakers understanding Mr Putin’s intentions and mindset today could not be more important. Predicting his response is pivotal in working out how far they can push him without triggering a dangerous reaction.

“Putin’s self concept does not allow for failure or weakness. He despises such things” says Ken Dekleva. “A cornered, weakened Putin is a more dangerous Putin. It’s sometimes better let the bear run out of the cage and back to the forest.”