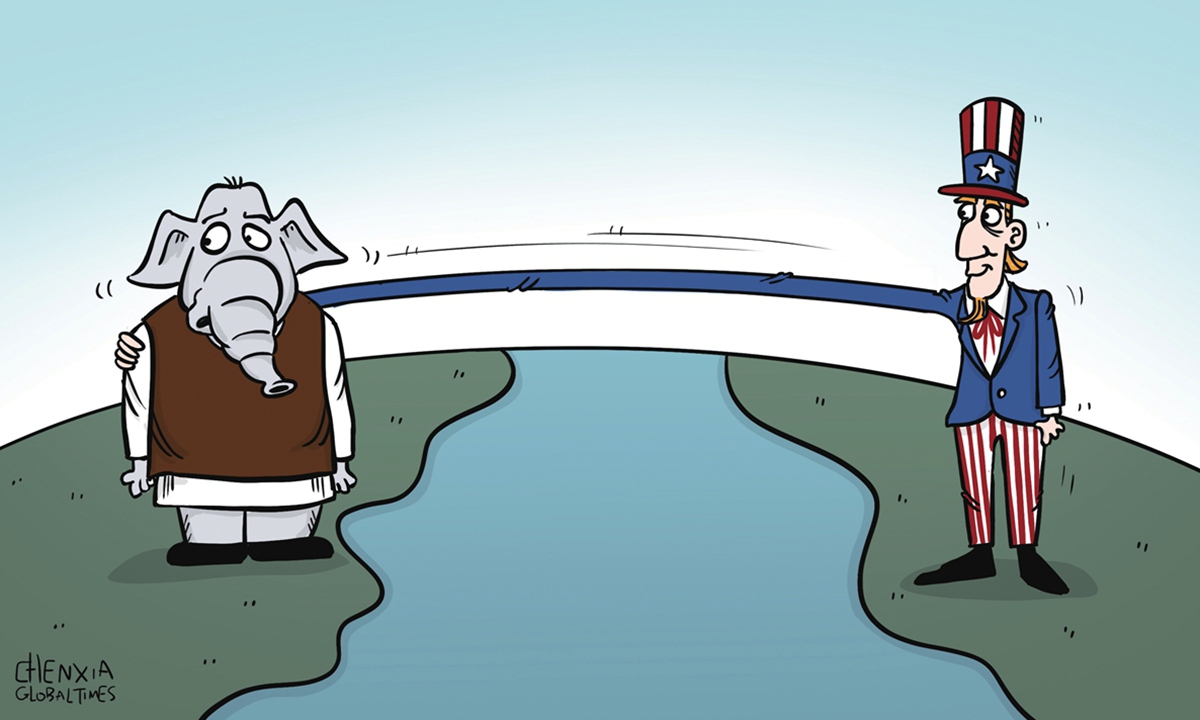

A state visit; a state dinner. If US President Joe Biden thinks this is enough to lure a country that has its own way of doing things, such as India, he has wildly miscalculated.

The White House announced on Wednesday that Biden would host Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi for an official state visit on June 22. A state dinner, one of the grandest of White House events honoring a visiting head of government, will also be included. Indian media noted that while Modi has visited the US during the terms of three US presidents in his nine years as prime minister, this is the first time he has been invited to a state dinner.

The timing of the visit is telling, according to Xie Chao, an associate professor at the Institute of International Studies, Fudan University.

The Quad will have a summit in Australia later this month, where leaders of the grouping will meet in person. In September, India will host the G20 summit. The US wants to extend the cooperation momentum of the small Quad clique to the big G20 multilateral platform, and win support from India on issues the US is concerned about, said Xie.

Long Xingchun, a professor at the School of International Relations at Sichuan International Studies University, echoes Xie’s view, as he believes that Biden inviting Modi to visit after the Quad summit shows Biden is not sure whether India would play a role in helping the US contain China and stand by the US in the Ukraine issue as Washington expects.

Since the Ukraine crisis broke out, India’s response has been distinctive among US allies and partners. While India maintains that such a balancing approach serves its interests, the US has been quite dissatisfied. To pressure India, the US has poked at India’s heart by approving a $450 million F-16 deal with Pakistan and removing Pakistan from the Financial Action Task Force’s “grey list.”

For the US and India, each knows what the other wants from it, and each also knows what it wouldn’t do for the other. Washington hopes to use India against China and Russia, while India wants to elevate its international standing by taking advantage of the US. Although the US is enticing India’s confrontation with China in border issues, India knows it too well that if it has a clash with China, the US will not come to its rescue. After all, the US cannot and will not decouple with China.

Meanwhile, India is too proud and ambitious to give up its major power dream. Allying too close with the US will put India in a submissive position and India will be forced to do things it is reluctant to do. Independence is something the US is too mean and stingy to give. India is looking at the UK and Japan — they are more powerful than India, but as US allies, they have lost independent diplomacy and their voices are not respected by the international community. Without independent diplomacy, how could India become a major power it desires Ram Madhav, national general secretary of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party, in an article on the Indian Express on May 6, called for “building a partnership of equals with the US.”

“The US is facing a dilemma: It tries to contain a rising power by seeking help from other powers, but it still wants to retain the ‘big brother’ demeanor in front of these powers, which is a demonstration of US’ declining strength,” Xie told the Global Times.

Even the term “democracy” can hardly tie the US and India together now. Asked about human rights concerns in India, White House Press Secretary Jean-Pierre told reporters that Biden believes “this is an important relationship that we need to continue and build on as it relates to human rights.” The 2022 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, released in March by the US State Department, listed significant human rights violations in India. In April, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said the US was monitoring “human rights abuses in India.” Modi is expected to face a lecturing from the US about human rights during his visit to the US, but Modi will obviously not buy it as these issues are determined by India’s domestic politics, according to Long.

The discord between the US and India has already been captured by Western analysts. Ashley Tellis, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, in a recent Foreign Affairs article, believed that Washington should harbor no illusion that New Delhi will join the US in any military coalition against Beijing. An article in the Financial Times on May 5 agreed with Tellis’ view, and added that another reason for India’s unwillingness to join the Western alliances is that “India has no wish to see a bipolar world or to be part of either camp.” This coincides with the repeated calls by Indian Minister of Foreign Affairs S Jaishankar for a multipolar world.

The Financial Times article noted that when Indian diplomats say India wants to see a multipolar world, that is exactly what they mean. Unfortunately, this is exactly what the US despises. The high-profile White House announcement of Modi’s visit to the US is the very proof that Washington and New Delhi appear intimate, but are divided in spirit.