By Jyoti Malhotra –SHER Bahadur Deuba has been elected Prime Minister of Nepal at an especially fragile time in the life of the 11-year-old Himalayan republic. Two years after the majority Madhesi population in the Terai blocked several trading points along the southern border with India, there remains deep-seated resentment in large parts of Nepal against the Kathmandu elite. Deuba inherits a divided Nepal, divided between the “dark-skinned” Madhesis and the “fair-skinned, upper caste Bahun-Chettris” of Kathmandu Valley, with whom New Delhi has been doing business since it bailed out King Tribhuvan in 1950.

By Jyoti Malhotra –SHER Bahadur Deuba has been elected Prime Minister of Nepal at an especially fragile time in the life of the 11-year-old Himalayan republic. Two years after the majority Madhesi population in the Terai blocked several trading points along the southern border with India, there remains deep-seated resentment in large parts of Nepal against the Kathmandu elite. Deuba inherits a divided Nepal, divided between the “dark-skinned” Madhesis and the “fair-skinned, upper caste Bahun-Chettris” of Kathmandu Valley, with whom New Delhi has been doing business since it bailed out King Tribhuvan in 1950.

But what is interesting in today’s Nepal is that India, which had supported the 2006 ‘jan andolan’ against the monarchy — which forced King Gyanendra to hand over power to the people — has all but abandoned the Madhesi agitation which was demanding exactly the same democratic rights. Which is, the right to be represented in Parliament and other state organs on the basis of population, or the one-man-one-vote principle.

Some would say that states must pursue power, and that in Nepal, power has always rested in Kathmandu Valley, not the Terai. And therefore, they would say, India cannot afford to take the high moral ground and continue to interminably support the Madhesis. No matter that Madhesis are 19.3 per cent of Nepal’s 28.5 million population or that half of them live in the Terai.

These people would argue that the Indian support of the rights of the Madhesis, and consequently the 135-day blockade they mounted from October 2015 to February 2016 to demand those rights, has run its course and that it’s time to turn the page. Forty five people were killed in the agitation, including one Indian national, and all of Nepal, especially the Terai, suffered terrible hardships as essential supplies grew scarce.

As the Kathmandu elite, then led by UML prime minister K P Oli, cosied up to the Chinese during the blockade, India watched uncomfortably. Certainly, it is this fear of the Chinese dragon expanding its cash-healthy presence across Nepal — including in the Terai plains which neighbour Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Haryana and West Bengal — that has forced India today to postpone the big fight on behalf of the Madhesis.

K P Oli began to openly woo both the Chinese as well as King Gyanendra when he suspected that the Madhesis may actually come into their own with the help of his former benefactor, India. Perhaps he forgot that Nepali Congress leader and former prime minister G P Koirala, with then Indian ambassador to Nepal Shiv Mukherjee as witness in 2008, had promised that Nepal’s Constitution would guarantee the Madhesis, Tharus, the indigenous tribes or Janjatis and others the same rights as the people of the “hills”, who have traditionally exercised power. But with the passage of the Constitution in September 2015, Oli and his fellow Kathmandu elite ducked. India watched with growing apprehension as Oli and his foreign minister, the pro-royal Kamal Thapa, promised the Chinese in March 2016 that they would allow them to open another consulate in the picturesque hill town of Pokhara. Beijing had already tempted Oli by offering him Nepali consulates in Lhasa and Guangzhou.

In addition, Oli agreed that the People’s Bank of China could open two more branches in the Terai, apart from the one it already had in Lumbini, where the Chinese are helping revamp the birthplace of the Buddha. The Chinese Northwest Civil Aviation Airport Construction Group is building the Gautam Buddha international airport in nearby Bhairahawa. Then Deuba’s predecessor, Pushpa Kamal Dahal or “Prachanda” — who knows India well since 2005 when he lived underground in the neighbourhoods of Delhi and Noida to escape the wrath of King Gyanendra — did something interesting. He put the Chinese bank projects on hold.

India, which had ironically played a key role in Prachanda’s dismissal in 2008-9 and helped Oli become prime minister, once again came out in support of the Maoist leader. It is no secret that Delhi, upset with Oli’s betrayal of Madhesi aspirations as well as his solicitations of the Chinese, persuaded its old ally, the Nepali Congress, as well as Madhesi parties to unseat Oli; soon it had brokered a rotating prime ministership between Prachanda and Deuba.

Deuba’s ascension to the PM’s chair last week, for the fourth time in his political life, is part of this Delhi-brokered agreement. But sometime midway during Prachanda’s tenure, Delhi lost its nerve on the Madhes issue, fearful that the Chinese were expanding their presence in India’s traditional sphere of influence.

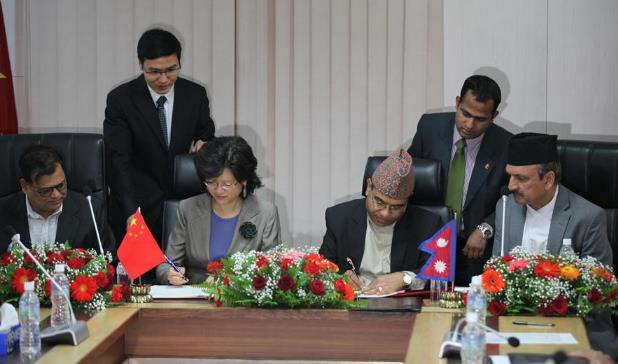

The Chinese were pouring money into Nepal, announcing projects everywhere, including in the Terai. Prachanda’s deputy prime minister, Krishna Bahadur Mahara, flew to Beijing to sign on the Belt and Road Initiative. For the first time, Nepal agreed that its defence forces would participate in exercises with the Chinese.

Meanwhile, after the Madhesi andolan ended on an indistinct note in February 2016, several Madhesi leaders went their own ways. Bijay Gacchedar and Upendra Yadav floated their own parties and fell in line with Kathmandu. Others, like Rajendra Mahato and Mahant Thakur, were persuaded by Delhi to form a coalition, the Rashtriya Janata Party of Nepal (RJPN), along with the smaller Madhesi parties. The argument being that strength lay in togetherness. But the truth is that the Madhesi street — in towns like Birgunj and Janakpur and Biratnagar — is furious that India has abandoned the its cause.

Barely two years ago, Delhi had shown the Madhes — and even at the time it was the people, rather than the political parties – a vision of democracy, however messy and chaotic. Travelling across the Terai during the blockade, this reporter was frequently told that “India’s democracy is our goal, where all people of all faiths and ethnic groups live together, equally. We want to be equal citizens of Nepal, as well,” they had said.

The fear of China, however, means that India has blinked on the egalitarian principle. Delhi hopes that Deuba, an able Nepali Congress leader, will amend the Constitution on the provincial boundary question as the Madhesis have long demanded; after all, the RJPN and others supported Deuba’s election on June 6.